The big North-South venture to solve the dark matter puzzle

Sourced by A/Prof Vanessa Panettieri, Editor (Educational), AFOMP Pulse

You’ve probably heard that (astro)particle physicists have been searching for dark matter for over three decades. What you might not know is that Australia is poised to play a unique role in this search in the coming years.

Dark matter refers to a new particle or particles beyond the Standard Model of quarks, leptons, and bosons. We strongly believe it exists because we can’t otherwise explain several gravitational phenomena across different scales. Without dark matter, we wouldn’t understand why peripheral stars in galaxies remain bound at high speeds, nor could we explain how galaxies move within clusters. The large-scale structure of the universe, which formed through gravitational collapse from a once-homogeneous cosmos, also points to its presence. Even the tiny temperature variations in the cosmic microwave background mapped in high resolution by modern satellites suggest dark matter’s influence. These low-energy photons are remnants of a pivotal moment in cosmic history (~400,000 years after the Big Bang), when the hot plasma of light and matter (both visible and dark) cooled and expanded into the universe we see today. From such observations, we can even estimate how much dark matter exists: a lot about five times more than visible matter!

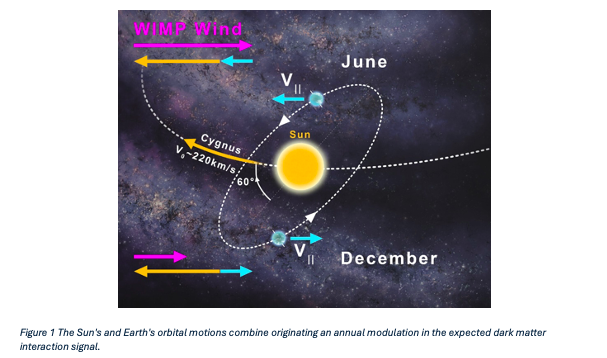

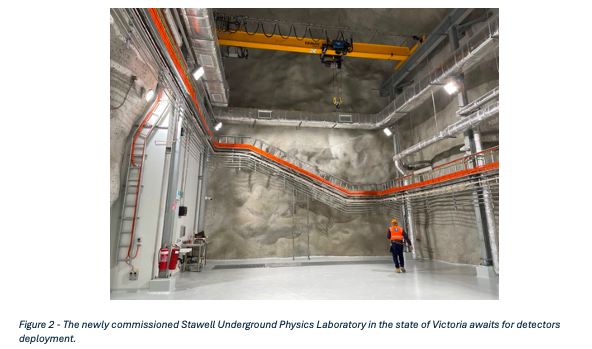

Yet, despite a global experimental effort, we have not yet detected dark matter’s interactions with ordinary matter. The leading hypothesis is that the Milky Way is embedded in a vast, spherical halo of dark matter. As the Sun orbits the galactic center at 220 km/s, we effectively move through this invisible sea, creating a steady “wind” of dark matter particles passing through us. While these interactions are rare, some must occur; otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to explain how dark matter formed. The goal of direct detection experiments is to observe these rare, faint interactions using increasingly large and sensitive detectors. To shelter from cosmic radiation, these experiments take place in underground laboratories this is where Australia’s newly commissioned Stawell Underground Physics Lab (SUPL), located in Victoria’s Stawell gold mine, is set to make a difference.

To understand why, let’s talk about the DAMA and SABRE experiments. While many experiments have reported null results, for over 20 years, Italian physicists of the DAMA experiment at Gran Sasso National Laboratory (LNGS) have observed an annual modulation in their NaI(Tl) scintillating crystal detector. They claim this is evidence of dark matter interactions. This could indeed be the case: its phase and period match the expected signal from dark matter, caused by the Earth’s motion adding to the Sun’s velocity for half the year and subtracting for the other half. However, other experiments using different materials and detection techniques have failed to find a compatible signal. This has sparked intense debate: is DAMA’s modulation caused by some seasonal environmental effect? All proposed explanations of this kind fail to account for the characteristics of the observed signal. And if it is really dark matter, is there a non trivial physics scenario at play, making direct comparisons between different target materials and techniques unreliable? With hundreds of papers published on this controversy, the only way to resolve it is to repeat DAMA’s experiment using the same detection method.

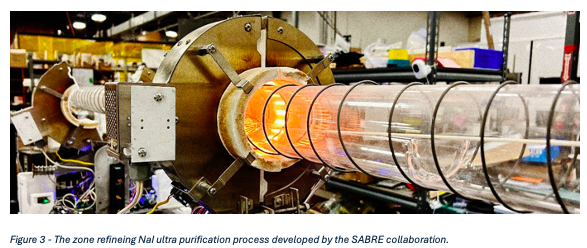

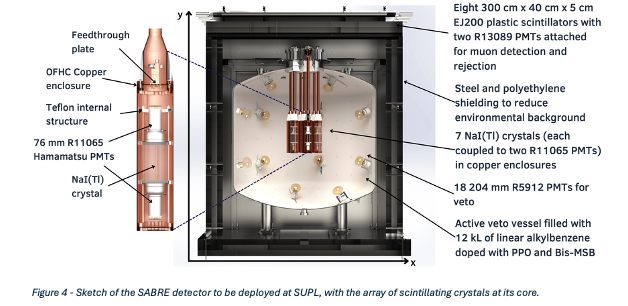

That’s easier said than done. Detecting such a faint signal requires materials with ultra-low levels of natural radioactivity. DAMA’s crystals, produced in the 1990s, were made using a proprietary purification process that has since been lost. After years of R&D and failed attempts, the SABRE experiment recently developed a new crystal-growing technology that may match or even surpass DAMA’s radiopurity. Mass production is now underway.

But here’s the catch: all underground physics labs are located in the Northern Hemisphere, buried in mines or under mountains. About ten years ago, when the SABRE collaboration was formed, a group of Australian research institutions (University of Melbourne, University of Sydney, Swinburne University, University of Adelaide, and Australian National University) joined forces with Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) to establish the Southern Hemisphere’s first underground physics lab at Stawell. The plan is to deploy two identical detector arrays one at LNGS and one at SUPL and analyze their data together. If DAMA’s signal is caused by seasonal environmental effects, it would appear with opposite phase in the two hemispheres. However, if the modulation is due to dark matter, the signal’s peak around early June should be identical regardless of location, as it depends only on the combined motions of the Earth and Sun.

Thanks to this North-South collaboration, we may finally be on the verge of resolving one of the most debated results in fundamental physics over the past 20 years.

Prof. Davide D’Angelo

Physics department

Università degli Studi & I.N.F.N.Milan (Italy)